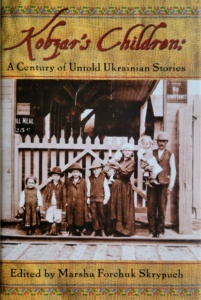

This unique anthology introduces new voices and a century of hidden stories.

This unique anthology introduces new voices and a century of hidden stories.

The kobzars were the blind minstrels of Ukraine, who memorized the epic poems and stories of 100 generations. Traveling around the country, they stopped in towns and villages along the way, where they told their tales and were welcomed by all. Under Stalin’s regime, the kobzars were murdered. As the storytellers of Ukraine died, so too did their stories.

Kobzar’s Children is an anthology of short historical fiction, memoirs, and poems written about the Ukrainian immigrant experience. The stories span a century of history; and they contain stories of internment, homesteading, famine, displacement, concentration camps, and this new century’s Orange Revolution. Edited by Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch, Kobzar’s Children is more than a collection; it is a moving social document that honors the tradition of the kobzars and revives memories once deliberately forgotten.

Preface

When I was a teen, I was an avid reader. I picked up all sorts of novels, short story collections and memoirs, but I was never able to find stories about Ukrainians who had come to North America. My Ukrainian grandfather died when I was in grade eight, and my grandmother died when I was in grade ten. But my father is a wonderful storyteller, and he did tell me all sorts of stories that his parents had told him. He also told me stories of his own childhood.

I longed to read books about Ukrainian immigrants, but I could not find any. I know, now, that there were stories. But they were written in Ukrainian, and because I couldn’t read or write Ukrainian, they were not accessible to me. One time, when I was about ten years old, I found a book about Cossacks in our local public library. It was the first and only time I found a story remotely about Ukrainians. I took that book home and read it cover to cover. I still remember the colorful illustrations of men with their tonsured hair flowing, riding their mighty horses across the Steppes. I took that book out of the library so often that it began to fall apart.

Because I couldn’t read about Ukrainians, I decided to do the next best thing. I read Russian stories, Polish stories, and Jewish stories. The stories plunged me into a different time and place and were very entertaining, but I began to notice a disturbing trend. Ukrainians were often portrayed with negative stereotypes. I noticed the same when I read North American stories about Ukrainians. While it was frowned upon to stereotype other ethnic minorities, why was it acceptable, and common, to portray people whose names ended in chuk, iuk, ski, and enko as buffoons, bullies, drunks, and murderers?

It wasn’t until I was an adult that I heard about the kobzars. These were the blind, wandering minstrels of Ukraine. The kobzars memorized long epic poems that had been passed down from generation to generation. These poems captured the rich history, the folk tales, and the cultural identity of Ukraine. When a kobzar came to a village, he was clothed and fed. And people gathered round to hear the tales.

During Stalin’s regime, kobzars were people who could pass information from one village to the next. Now, the older tales were intermingled with contemporary stories of Soviet repression, famine, and terror. Stalin heard about these kobzars, and he was not amused. In the 1930s, he called the first national conference of kobzars in Ukraine. Hundreds congregated. And then Stalin had them all shot.

As the storytellers of Ukraine died, the stories died too. But Stalin wasn’t content with this. He rounded up Ukrainian journalists, artists, novelists, and playwrights, and murdered them, too.

The word “kobzar” resonates for another reason. Kobzar is the title of Taras Shevchenko’s first collection of poems, published in 1840. Taras Shevchenko was born a serf in Tsarist Russian controlled Ukraine but rose to be Ukraine’s most beloved poet and artist. He suffered censorship and exile in his lifetime for writing about the rich history and culture of Ukraine. He is popularly known as The Kobzar. During Stalin’s time, Shevchenko’s writings were deliberately falsified.

Some Ukrainians did escape the Stalin terror. And some of them immigrated to North America. But these immigrants were not writers. They were farmers, pharmacists, engineers, and coal miners. Even now, although there are millions of North Americans whose roots are in Ukraine, only a handful of them are writers. My passion is to write stories that capture real experiences that have been suppressed or lost. That’s why I often write about Ukrainians. When you don’t write your own stories, someone else will write their version for you.

After I published a few books touching on Ukrainian history, people began to contact me by e-mail, telephone, and letter. Thank you for writing my story, one letter said. It is time that the record has been set straight, said another. Others wrote, I have a story, too. After a while, I gathered together people who had stories and started up a small e-mail critique group. It was through this group that most of the stories in this collection have emerged. They are arranged in chronological order, beginning with an early homesteader tale in 1905 and ending with a story set during the Orange Revolution and the election of Yushchenko in 2004.

We are the Kobzar’s Children. Our parents and grandparents suffered in silence, with their life stories and histories either suppressed or falsified. This anthology tells a century of untold stories. I hope that after you read this book you will be inspired to talk to someone whose stories have been deliberately forgotten, because the injustices that we forget, we are bound to repeat.

Reviews:on CM:

“Social injustice and the mistreatment of Ukrainian people, both in Europe and in Canada, are brought to the fore in this moving book that not only will revive some memories but will also ensure that the truth is told and the stories will not be forgotten. A fitting tribute to the resilience of the Ukrainian people, this book is long overdue. Dyakoyu, Ms. Skrypuch! Highly Recommended. (4/4)”

Victoria Pennell on Resource LInks wrote:

These stories and poems, written by descendants of the Ukrainian immigrants, tell stories of homesteading in a new land, of internment during World War I, of famine, displacement and concentration camps in the Ukraine, of refugee camps and of the Orange Revolution of 2004 which gave a new era of democracy to the country. This book will be a useful adjunct to the study of immigration and multiculturalism in Canadian social studies programs. It will also be of interest to the Ukrainian descendants who have never heard these stories before.

on Winnipeg Free Press:

“The anthology succeeds in providing a broad overview of a century of the Ukrainian immigrant experience.”

on Amazon:

“I couldn’t put the book down. I frankly had expected a charming work aimed at children, but how mistaken I was. Although this book is suitable for all ages capable of reading at this level, it is of no less interest to the adult reader as to the young reader. It never talks down to its audience. In the same way that I remember my own parents relating the many stories of our family, no punches are pulled. Harsh reality and horror and danger take their place alongside tales of humor, childhood pranks and misunderstandings.”

on Barnes and Noble:

“This collection of stories was truly a labor of love, borne of the author’s lifelong hunger for stories about Ukrainian immigrants like her forebears. Here, gathered together in the pages of a single volume, are stories covering nearly a hundred years of Ukrainian immigrant history, from 1905 to 2004. The stories occur in a variety of settings, from homesteads to cities, internment camps to nursing homes, Ukraine to Canada, and more. Find out how Ukrainian immigrants were treated by Canadian officials during World War I, discover how one boy lost his entire family but somehow escaped from the 1932—1933 Famine-Genocide, and chuckle about one lad’s desperate longing for a pair of red boots to wear at a community concert. Read about a farm girl’s prank, walk along with a refugee during World War II, and think about the significance of the recent Orange Revolution. And it’s all within the pages of this slender book. In this and earlier works, Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch truly continues the tradition of the kobzars, traveling storytellers who collected and shared the stories of the Ukrainian people. Her works are always educational and informative, recounting tales and times that have been ignored and forgotten, but they are certainly never, ever dull”