This interview used to be available on the Chapters-Indigo site, but it was recently removed, so I am posting it here:

This interview used to be available on the Chapters-Indigo site, but it was recently removed, so I am posting it here:

Interview Questions for Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch by Melanie Fishbane for Indigo.ca

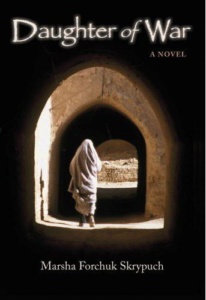

1) How is Daughter of War different from its predecessors, The Hunger and Nobody’s Child?

Daughter of War begins where the other two novels leave off. At the end of Nobody’s Child, Marta is pregnant, but we don’t know who the father is and we also don’t know if she and Kevork will get back together. Worse, even if they do get back together, how will Kevork react when he finds out that she is pregnant with another man’s child?

Daughter of War covers the middle period of the Armenian Genocide – from about 1916 to 1918. Nobody’s Child concentrates on 1915 and The Hunger concentrates on 1909.

2) Did you know that you would be writing a trilogy when you started to write The Hunger?

I had no idea. I did know that I had a lot more story in me though. Kevork, Marta and Mariam have been in my head for 20 or more years. There is a fourth book in my head right now, which will bring the story to 1923 and their expulsion from Turkey and their immigration to Canada.

3) If I am remembering correctly, in each book, you seem to focus more closely on one particular character. In Nobody’s Child, Mariam seemed to be the dominant voice, whereas in Daughter of War, it is her sister Marta that we hear more about. Is this because you were trying to write more of a love story?

In Nobody’s Child, the narrative alternated between Kevork and Mariam. In The Hunger, the point of view was Marta’s. I wasn’t thinking in terms of a love story at all. The reason that much of Daughter of War is from Marta’s point of view is because it’s her daughter – Pauline – who is the daughter of war. Marta has some pretty big issues to grapple with and I think that a lot of young adults today are dealing with some of the same issues. Yes, this is a love story, but it’s not a romance.

And just like Nobody’s Child, Daughter of War has alternating narratives. The two main ones are Marta and Kevork, but some scenes are from the point of view of secondary characters as well.

4) When you were writing your most recent novel, Daughter of War, were you expecting it to be aimed at a different audience? What do you think about making a transition from children’s to adult fiction?

I don’t think of any of my novels as for a particular audience. I write what my characters tell me to. I think that Daughter of War will appeal to teens every much as Nobody’s Child and The Hunger. But judging from the letters I get, adults have always read my novels as well.

5) What is the challenge that you find when writing about very difficult (and often violent) circumstances?

I often find myself in tears. Sometimes I have nightmares. I need to let these stories unfold so that these people who have been silenced by the injustices of history can be understood and respected. It’s a catharsis for me. It is an honour for me to bring these people back to life so that readers can understand the circumstances of history and understand how these awful things could have happened. I know it’s trite to say, but we must remember the past so that we don’t repeat it.

6) How old do you think it is appropriate for children to learn about genocide and in what context?

Early elementary aged children can be introduced to the concept of genocide on a simple level. There are gentle ways of handling it, for example, how I dealt with it in my picture book, Enough. Genocide is the ultimate bullying – and bullying is something that very young children are forced to understand from first hand experience. Learning about genocide in the context of bullying brings it down to an individual level.

7) You have written many books for a variety of ages. In particular, Enough is aimed for a younger audience whereas The Hunger is certainly for an older age group. How do you approach your writing and the subject matter so that it is appropriate for the reader?

When I begin a book, I think of the story, rather than the audience. Once the characters develop in my imagination, I have an idea of who the audience might be. If the story has a folk tale element, like Silver Threads or Enough, even difficult topics can be broached in a way that evokes empathy rather than fear.

One thing to keep in mind though is that picture books like Enough and Silver Threads appeal to adults and young adults as well as children. An older reader can appreciate these stories on one level, while a child will be attracted to a different layer.

8) Reading your autobiography on your website and other interviews, you were misdiagnosed as “slow” as a child because you didn’t read until you were in grade 4. Can you speak on how this has influenced your writing?

My own early experiences with books and reading made me the writer that I am. It wasn’t that I couldn’t read when I was young, it was that I opted out of reading. I saw no point to it. I was in elementary school in the 1960s and in that era, there was the assumption that children were stupid, therefore, to teach them to read, one must provide them with stupid books. I have never officially been diagnosed with a learning disability, but teachers today have told me that I likely have a form of dyslexia. While a regular child would be able to pick up a simple picture book like See Spot Run and learn to read with it, I couldn’t. There was nothing in the book to show me where it started and where it ended because I have no sense of direction and See Spot Run has no story. Even today, I have a tendency to read the newspaper backwards and I have a GPS in my car. The only thing that can propel me forward in a book is the story. Educators of my childhood didn’t think learning to read had anything to do with story, so the school books I was forced to read inoculated me against reading.

I have a visual memory, and so I had memorized many words so when I got up in class to do oral reading, I would just use my memory rather than sounding out. This worked brilliantly in the early grades but it caught up with me in grade four when I failed my provincial reading/writing test. When I was in grade four for the second time, I decided that I had to bite the bullet and just learn to read the usual way – ie – sounding out words rather than relying on memory and context. The first book that I read was Oliver Twist. It took a whole year to get through it, but unlike those simple texts like See Spot Run, there was a story that propelled me in the right direction. I sure couldn’t read that book from the back to the front!

But it also showed me that reading wasn’t all about words and it wasn’t like other subjects in school. It was entertaining. It was free movies in my head. I decided at that point that when I got older, I would write books. I wouldn’t write the ones that assume the reader is stupid like See Spot Run. I would write books that were respectful and intelligent, and could be appreciated by kids and adults alike.

I write the books that I would have liked to read when I was a kid and a teen.

9) On your website you have various links to advocacy groups for breast feeding. Can you speak more about your work with these organizations?

I don’t do much active advocacy with breastfeeding groups anymore, but before I began writing, I had invented a washable breast pad for nursing mothers. That breast pad was sold in many countries around the world in the 1980s and 1990s and most washable breast pads on the market today are based on the one that I invented. I also wrote a book for toddlers that was published in 1998 called The Best Gifts. It’s about all the things we do with our children that mean the most – breastfeeding, reading a book together, playing together. The best gift is of course spending time and love with your child. This gift doesn’t come in a bright shiny box, but it’s the one that has the most profound effect on a child. This book was adopted by La Leche League International and is still a favourite with new parents.

10) Recently, you were awarded the Order of Princess Olha from the President of Ukraine. What was that like for you to receive this for your writings on the Ukrainian Famine (Holodomor)?

I was blown away. When my picture book, Enough, came out in 2000, I received hate mail and death threats. It was a scary time for me. Back then, it was acceptable to deny that 10 million Ukrainians had been intentionally starved to death on Stalin’s orders. I must have angered pro-Stalinists by writing a picture book about one girl and her father and how they saved one village from the Holodomor. Receiving this honour shows that the truth does win out if you’re patient. I hope it is an indication that people now realize that Stalin was a mass murderer on the scale of Hitler.

11) When you do author tours to school libraries, panel discussions, or book store signing events, which event to do find most rewarding? Do you find that you have a real chance to connect with your readers?

What I love best is doing school visits. There is nothing more satisfying than going into a school library filled with kids and discussing my books. I also love talking about my own early learning struggles and seeing how that connects with students in the audience. There are always students who hate reading and I like to address that issue head-on, because I was just like that in elementary school.

12) Do you find that writing in a particular period of time confines the ways in which a character would behave that might have been different than you would have preferred them to behave?

I never tell a character what to do. I research the era exhaustively, and then I carefully construct my characters. Then all I have to do is let my characters loose in that world and follow behind with my keyboard, writing down everything they feel and see.

13) Do you have any authors right now that you admire and would recommend to our readers?

I have many favourite authors. I love everything that Lynne Kositsky writes. My favourite novel of hers is The Thought of High Windows. I also love Gillian Chan and my favourite of all her novels is her Dear Canada novel, An Ocean Apart. I also love Barbara Haworth Attard’s books, especially Theories of Relativity, and Karleen Bradford’s Angeline. I am anxiously awaiting kc dyer’s next novel, coming out with Doubleday Canada. She wrote a wonderful time-travel trilogy, The Seeds of Time/Secret of Light/Shades of Red. An American writer whose words sing is Linda Gerber. Her most recent novel is Death by Bikini. And Kate Coombs, another American, has clever and humourous books. I especially love her children’s novel, The Runaway Princess. Someone who blows me away by his brilliance is James Bow. He is only in his 30s, yet his novels are wonderful. And he’ll only get better. I also love Pat Bow, James’ mother. Her newest novel is The Prism Blade and I look forward to reading it.

Another new writer who has impressed me is Marina Cohen. She has two SF/fantasy children’s novels out called Trick of the Light and Shadow of the Moon. And Mahtab Narsimhan is another promising new author to watch. Her first novel, The Third Eye, is rich and action packed.

I am a huge fan of Philip Pullman. I loved His Dark Materials. I also love JK Rowling. As for adult fiction, I love thrillers. My favourites are Greg Iles, John Katzenbach, Stephen White, Mo Hayder, John Sandford, Michael Connelly, and Douglas Preston/Lincoln Child.